Abstract: Authors describe the mixed-methods evaluation approach used by Connecticut’s CT STRONG program, and the measured improvement in mental health symptoms, perceived stigma, social connectedness, and empowerment among its participants.

"Preliminary Outcomes in CT STRONG: A Youth and Young Adult Wraparound Program" (2019)

Eleni Rodis, Jennifer C. Donnelly, Karen Hensley, & Dawn Grodzki

Over the past four years, youth and young adults have been participating in the CT STRONG program, Connecticut's Healthy Transitions project. CT STRONG (Seamless Transition and Recovery Opportunities through Network Growth) involves a Wraparound model utilizing peer support and family advocacy and serves a population of transition-aged youth and young adults, ages 16 to 25, who have, or are at risk for, behavioral health disorders and who live in three Connecticut towns. The program engages and connects them to high quality behavioral health services and supports. CT STRONG utilizes innovative approaches while implementing the key principles of the Wraparound approach, but is very flexible to meet the needs and preferences of young people.

Evaluation Methods

The evaluation of the program involves both quantitative and qualitative components in order to capture both outcome and process measures:

- Staff-Client Activity Logs: A log of staff activities is used to record client-related contacts and types of assistance offered on a weekly basis.

- Client Interviews: Clients are interviewed at three time intervals: intake/baseline, 6 months, and 12 months after intake. Scales of Special Interest – The client interviews include all of the data required by SAMHSA's GPRA instrument.1 The CT STRONG team added items focused on variables of special interest; namely, youth empowerment, late adolescent connectedness, and stigma.2,3,4,5 The evaluators and young adults with lived experience developed these measures by selecting and modifying items from existing scales.

- Focus Groups: Several focus groups were held with clients and program staff to identify key program components as well as barriers to and facilitators of implementation, and to better understand the quantitative findings.

Preliminary Results

The evaluation is ongoing, so all results should be considered preliminary.

I. Weekly Logs

The CT STRONG team uses weekly activity log data to describe the frequency, intensity, and types of services being provided by staff, which reflect what the greatest needs are for the clients. To date, they have received 3,279 logs for 299 clients.

The top activities reported include emotional support for clients and families; advocacy; peer support; crisis management; and engagement in treatment planning. Over a third of the clients have been referred to formal mental health services.

Another frequent activity is teaching transitional life skills, of which vocational and money management skills are the most common. Program staff have provided emotional and parenting support for about a third of the family members of CT STRONG clients. Occasionally, staff have also helped family members apply for benefits or obtain community services.

Transportation is the fifth most common weekly activity that staff provide or help arrange for, and is often reported as a need for the clients.

Program staff also assist clients with benefit and ID applications. Assistance with housing subsidies, Medicaid, driver's licenses, and SNAP benefits were most commonly reported. In addition, CT STRONG clients received help obtaining a variety of basic needs, including personal care items, food and clothing.

II. Interview Data

A total of 193 baseline, 109 6-month, and 78 12-month interviews were completed at the time of this analysis. Some significant limitations to the completeness of the interview data given by young people include a higher refusal rate for participating in interviews than most adult populations. (The 6-month follow-up rate has been approximately 66% in recent months.) Nevertheless, given the large number of interviews available, some preliminary observations can now be noted.

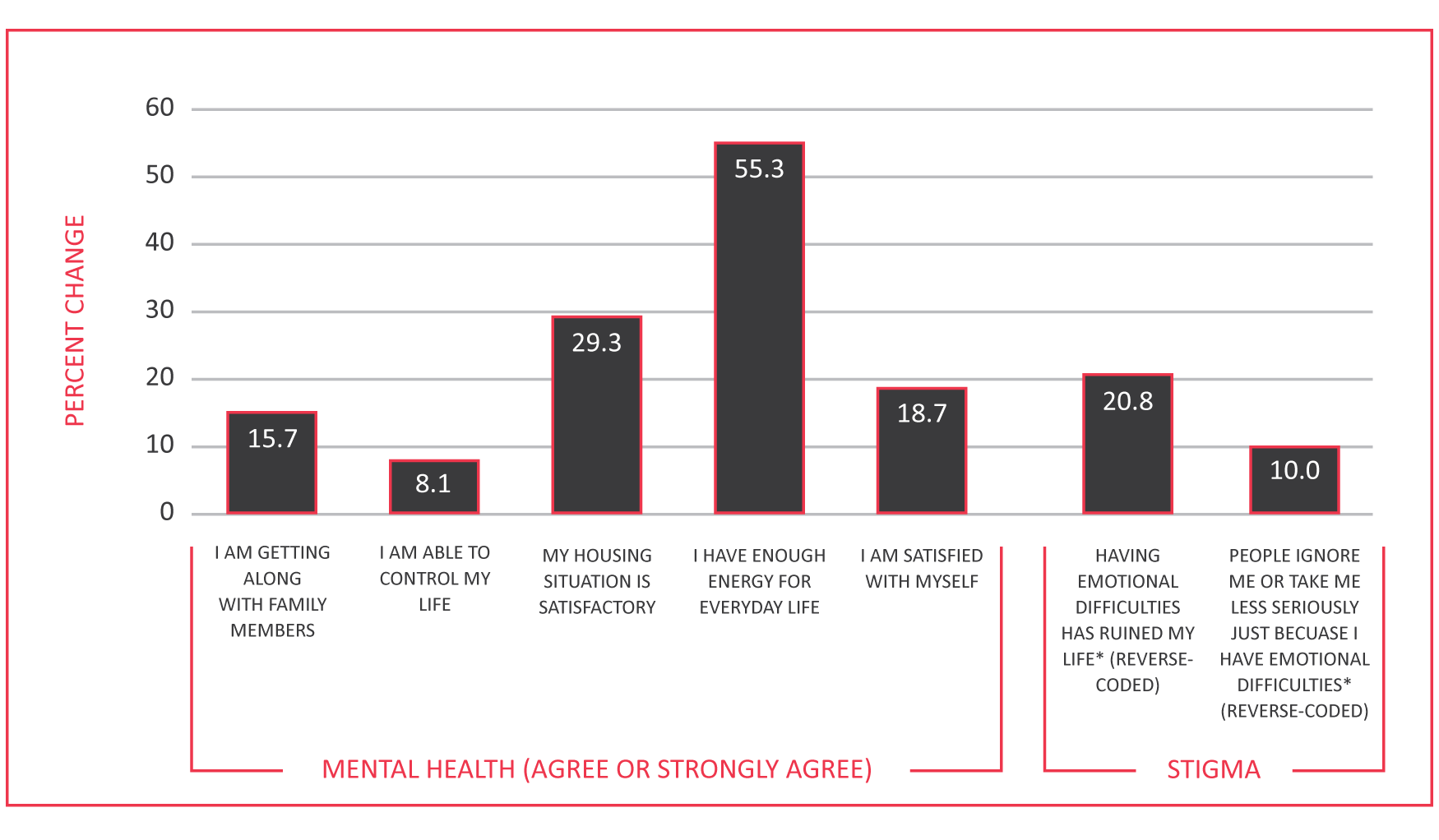

Due to the lower number of 12-month interviews currently available, only baseline and 6-month data were included in the analysis. The interview data suggests some preliminary positive outcomes when comparing baseline to 6-month scores on several measures. Positive outcomes include an improvement in mental health and reduction in perceived stigma around emotional difficulties (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mental Health and Stigma: Percent Change from Baseline to 6 Months

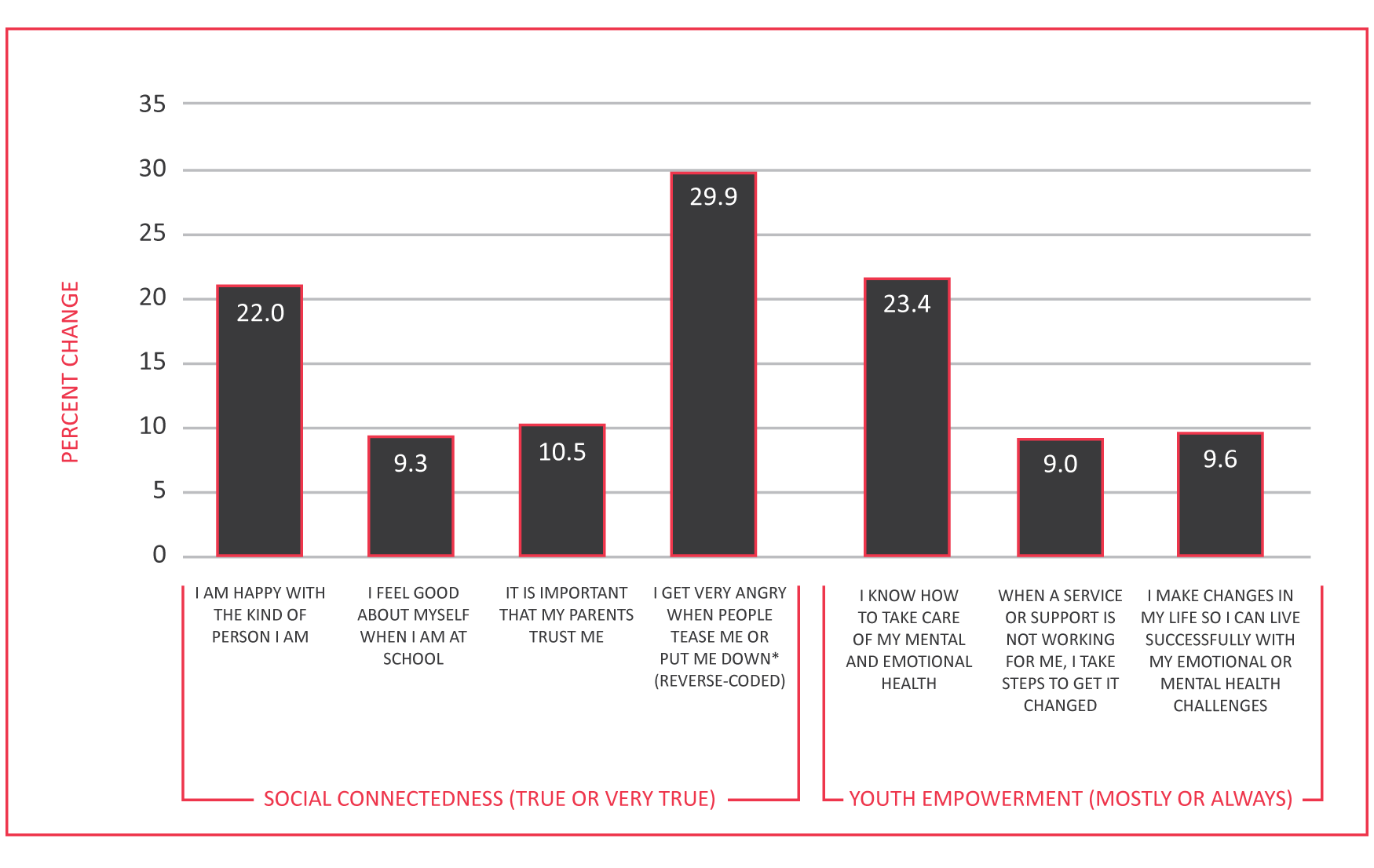

Improvements in social relationships, self-esteem, and empowerment around managing their health and services were also noted (See Figure 2).

Figure 2. Social Connectedness and Youth Empowerment: Percent Change from Baseline to 6 Months

Positive housing outcomes are also indicated. The percentage of participants who owned or rented a house or apartment nearly doubled from baseline to 6 months (17.1% to 31.7%). The percentage of participants who reported living in an emergency shelter or in a place not meant for habitation decreased (5.7% to 1.0%).

III. Focus Group Feedback

Two of the main findings from the client focus groups were: program staff meet the clients "where they are" by first working on what clients identify as their immediate needs and goals; and the clients are very enthusiastic about the program, want more people to know about it, and want more programs like it to be set up. Young adults appreciate the program flexibility to focus on their goals. Self-identified main needs are: jobs, education, support while in school/college, independent housing, advocacy, knowledge of rights, and help getting into services. CT STRONG has assisted them with finding jobs, getting driving permits, and looking into colleges and financial aid. One participant noted, "Yeah I think the first day I came in here, me and one of the staff – we sat down and we filled out almost ten (job) applications in the first day of being here." There was a consensus that the participants feel like they can trust the staff, with participants saying, "They keep your personal stuff personal," and "They respect you 100%."

The peer group participants generally described having had mental health problems since childhood, especially as related to trauma. Most have a history of service use and are currently in other mental health services. The young adults identified stigma as a barrier to receiving mental health services. They mentioned that the fear of stigma often prevents young people from getting help or talking about what is happening. They have noticed that there is less stigma in younger generations but reported that their parents often do not understand mental illness. One participant shared, "For me, I consider my [mental illness] experience as one small chapter of my whole book."

All seemed to have had mixed experiences with mental health services, including having found some mental health professionals they trusted and others they didn't. Many expressed appreciation for receiving trauma-specific services. Generally, they wanted their preferences to be heard and solicited rather than having services based on assumptions and cookie-cutter recommendations (e.g., based solely on diagnosis). Although some found relief for their symptoms with medication, they didn't want medication to be assumed to be the best course of treatment. There was a strong preference for non-traditional/non-medical approaches such as yoga and meditation.

The young adults attending the peer support groups have found the experience to be very positive:

"We do have deep conversations about what we're going through… And we'll give words of encouragement to everybody… It's a very nice environment and it's safe for a lot of people. So I like it a lot."

"It's definitely something I look forward to in the week… it's definitely something I'd rather have more often than just once a week."

Many participants discussed making friends in the group.

"Some of us hang out outside of group. I would say that a lot of people I'm pretty close with, I met in this group."

Recommendations from participants included the following: There should be more young adult support groups and parent education/training across the state. Mental health providers should not judge youths' or young adults' capabilities based on their worst days.

Discussion

Preliminary results suggest that peer support and a youth-centered, flexible Wraparound approach have led to improvements in the lives of individuals in the CT STRONG program. A mixed method evaluation approach is needed in order to capture a full picture of both process and outcome measures for the transition-aged youth and young adult population.

References

- Center for Mental Health Services (2017). NOMs client-level measures for discretionary programs providing direct services. Services tool for adult programs. SPARS Version 2.0. Retrieved from https://spars.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/CMHS_Client-Level%20Services%20Tool%20for%20Adults.pdf

- Boyd, J. E., Otilingam, P. G., & DeForge, B. R. (2014). Brief version of the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale: Psychometric properties and relationship to depression, self-esteem, recovery orientation, empowerment, and perceived devaluation and discrimination. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 37(1), 17–23.

- Karcher, M. J., & Sass, D. (2010). A multicultural assessment of adolescent connectedness: Testing measurement invariance across gender and ethnicity. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 57, 274–289.

- Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G., & Hackler, A. H. (2007). Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: The mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(1), 40–50.

- Walker, J. S., Thorne, E. K., Powers, L. E., & Gaonkar, R. (2010). Development of a scale to measure the empowerment of youth consumers of mental health services. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 18(1), 51–59.

Suggested Citation

Rodis, E., Donnelly, J. C., Hensley, K., & Grodzki, D. (2019). Preliminary Outcomes in CT STRONG: A Youth and Young Adult Wraparound Program. Focal Point: Youth, Young Adults, and Mental Health, 33, 15–19. Portland, OR: Research and Training Center for Pathways to Positive Futures, Portland State University.